(Above) Turn Me On, by Jack W. Thomas (Bantam, 1969)

(Above) Turn Me On, by Jack W. Thomas (Bantam, 1969)

I spent a good deal of my early writing career banging away on typewriters, discarding heaping piles of crumpled draft pages as I went, and then seeing my work cemented into print publications, whether they be books, magazines, or newspapers.

While most of that process was satisfying, even rewarding, there is one thing about composing for print vehicles that gives me nightmares: If I accidentally make a mistake—and I’ve made a few in my time—it’s permanently recorded. I can’t go back into a printed magazine or newspaper and quietly correct a misspelled name, a misstated date, or a particularly egregious typo. In a book, I can at least try to revise any error in a second edition (if there is one). But otherwise, my minor editorial blunders on paper are recorded for perpetuity, even if I’m the only one who notices them.

Thankfully, such frustrating obstacles don’t exist when one is writing for blogs or other Web-based periodicals. Small fixes can easily be made, and there’s no need to draw reader attention to them (though some sites do post classic-style “corrections” at the end of amended pieces). Many have been the times I’ve gone back into older posts in either Killer Covers or The Rap Sheet, and rectified erroneous spellings of author names or other tidbits of information.

Just recently I righted a different sort of wrong.

Almost two months ago, I presented on this page a gallery of 13 Mitchell Hooks paintings that fronted “teenager-in-torment” novels. However, I later learned that one of those images—the cover from the 1968 Bantam Books edition of Please Don’t Talk to Me, I’m in Training, by novelist and screenwriter Robert Kaufman

(1931-1991)—wasn’t done by Hooks at all. Instead, it represented the work of his fellow artist, James Bama. (You can see his signature, below, in the illustration’s lower right-hand corner.)

(1931-1991)—wasn’t done by Hooks at all. Instead, it represented the work of his fellow artist, James Bama. (You can see his signature, below, in the illustration’s lower right-hand corner.)(Left) A young James Bama

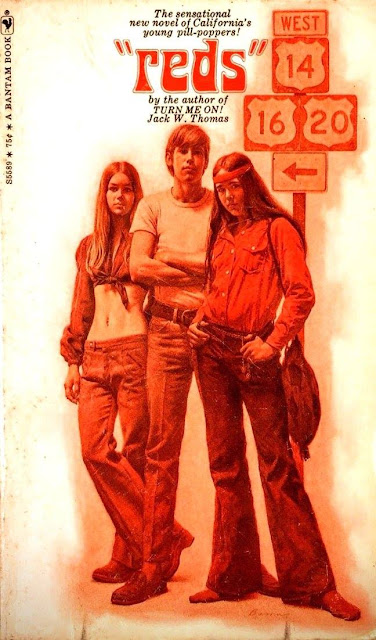

I quickly—and surreptitiously—replaced Kaufman’s swinging love story in that lineup with the 1962 Gold Medal release For the Asking, by Harold P. Daniels, which sources agree was a Hook creation. Only then did I realize that Bama, too, had contributed artwork to a variety of paperback novels about mid-20th-century teenagers either causing trouble or trying to find their own way in a confusing new world of sex, drugs, and yes, rock ’n’ roll. Nine examples of his efforts along that line are showcased here. They include his front for a 1967 Bantam release of Robert H. Rimmer’s The Harrad Experiment, a controversial yarn (originally published in 1966, and made into a 1973 film) about sexual experimentation at a made-up college; and his painting for Groupie (Bantam, 1970), a fictionalized account of London’s 1960s “underground music scene,” by Jenny Fabian and Johnny Byrne.

Several of these paperbacks come from what books historian Lynn Munroe calls Bama’s “White Bantam” series, meaning they feature human figures on white backgrounds. And almost half of them suggest the New York-born artist appreciated the bare-midriff look popular with young women in the 1960s and early ’70s.

FOLLOW-UP: Not long after I posted this cover gallery, Robert Deis, who writes the wonderful Men’s Pulp Mags blog, and who has interviewed artist Bama in the past, sent me this message: “The model Jim Bama used for some of his best-known ‘troubled youth’ covers was Andrea Dromm. She was also an actress, who is probably best known for a part on [the original] Star Trek.” Deis attached a set of photos—see below—showing Dromm in poses that later inspired Bama’s paintings for Tomboy (1965) and The Heller (1970).

Click on the image for an enlargement.

1 comment:

Thanks for the shout out. I love the Killer Covers blog -- and Lynn Munroe's website.

Post a Comment