X marks the spot--twice! On the left is the 1952 Avon paperback edition of The Tragedy of X, written by cousins Manfred B. Lee and Frederic Dannay under their alternative nom de plume, Barnaby Ross. (Lee and Dannay were, of course, much better recognized for their many novels bylined “Ellery Queen.”) The Tragedy of X was originally published in 1931 and was the first of four novels featuring Drury Lane, a retired performer and rather brilliant amateur sleuth. This is how the essential online resource, Ellery Queen: A Website of Deduction, describes that book’s plot:

New York City, the early 30’s. A man is poisoned on a crowded streetcar during rush hour. Everyone saw him die, but no one saw the killer! And far too many people had good reason to hate Longstreet. The few clues lead up to a blind alley, and District Attorney Bruno and Inspector Thumm pay a call on Drury Lane.Not everyone finds this yarn impressive. Indeed, the pseudonymous blogger at In Search of the Classic Mystery Novel--who’s quite well read in Queen’s oeuvre--says he was “disappointed” by The Tragedy of X. “There’s a critical part of the solution,” he writes, “that is blindingly obvious, which pinpoints for Lane the criminal almost immediately ... [but] is completely overlooked by the police characters. In fact, it’s so obvious that the reader may assume that it isn’t important to the solution of the crime--i.e. that the authors overlooked it themselves--but in fact it makes Thumm and company look like absolute morons for not considering it. One part that is overlooked is how anyone, including the victim, did not notice the weapon being put in the victim’s pocket.”

Drury Lane! Retired Shakespearean actor. Matinee idol. Master of disguise. Amateur sleuth who finds “crime the highest refinement of human drama.” Ellery Queen’s most flamboyant creation.

Seated amid the splendor of the vast medieval halls of his castle on the Hudson, Drury Lane hears the story. Almost at once, he knows who the murderer is, but refuses to reveal his identity until he has sufficient evidence for the police to arrest him.

In the great tradition, all the clues are scrupulously presented to you, the reader. Can you solve the case before the police?

Almost as significant a letdown is that the cover artwork on this 1952 edition of Barnaby Ross’ X--which apparently shows the shocking discovery of Longstreet’s corpse--is uncredited.

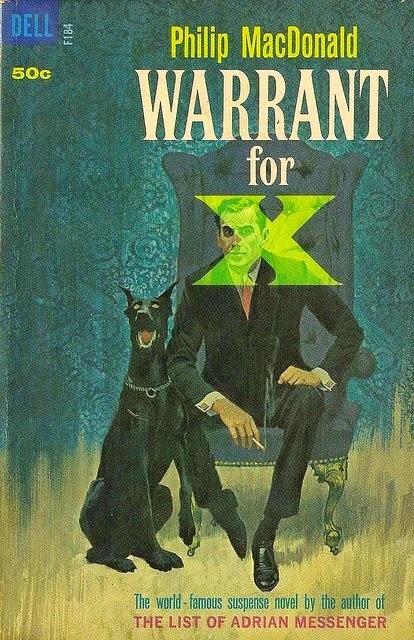

That’s certainly not the case with the book front highlighted above and on the right. Taken from the 1962 Dell edition of Philip MacDonald’s Warrant for X, it bears an illustration by the great Robert McGinnis. And though that painting seems to portray a young Gore Vidal in a chair, with a Doberman Pinscher at his side, I have to assume that was not intended.

Warrant for X was first released in 1938 under the title The Nursemaid Who Disappeared, and was the second-to-last in a series of a dozen novels starring amateur crime-solver Colonel Anthony Gethryn. One writer sums up the story in this manner:

Warrant for X documents a very clever idea that is at the base of this clever novel. An American playwright is in a teashop and overhears the conversation of two women (whom he cannot see) who are apparently planning a crime. One, with a deeper crueler voice, is intimidating the other, with a higher, more gentle voice. He catches a glimpse as they leave of a short stumpy brunette and a tall slender young blonde. And one of them leaves a glove behind that contains what seems to be a scrawled shopping list.British author Philip Macdonald, who died in 1980, is probably best remembered by people like me, who go out of their way to read broadly in the crime/mystery genre. But some folks may not even know they’ve had experience with his work, when they have. After all, Macdonald’s last Gethryn tale was 1959’s The List of Adrian Messenger, which was turned into a popular and well-respected 1963 film of the same name starring George C. Scott.

This is an early example of what one might call a proto-police procedural, or perhaps if one allows such a sub-genre to contain amateurs acting like police this designation makes more sense. The playright takes his suspicions to the police and is pretty much turned away, so he enlists the assistance of well-known detective Anthony Gethryn (whose adventures also began with The Rasp). Together, they piece together crucial details from the few details offered by the playwright and from the shopping list, which turns out to contain much more information than one might have thought, and learn that a child of wealthy parents is going to be kidnapped with the assistance of her nursemaid. And the book moves to an exciting finale, once the police get involved.

1 comment:

This is a great post. Wonderful background on both books.

I do love the Philip MacDonald book with that great cover. I will look around for a decent copy.

Post a Comment