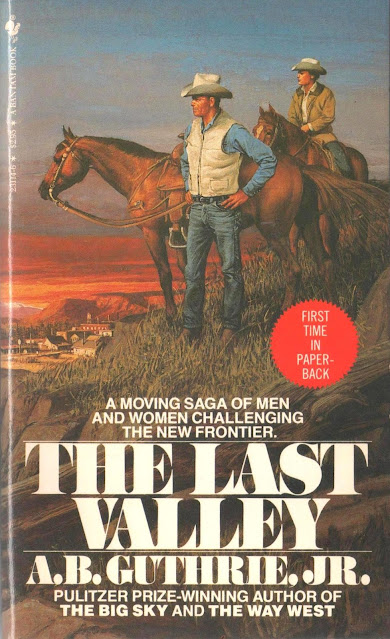

Fair Land, Fair Land, by A.B. Guthrie Jr. (Bantam, 1984).

Cover illustration by Louis S. Glanzman.

There was a time, back in my lonely youth, when I reread books almost as often as I devoured new ones. But over the last decade, it’s become rare for me to dive into a work I previously enjoyed. This has much to do with the fact that I review more books nowadays than I once did, so I’m always chasing what’s fresh and foremost on bookstore shelves. Rarely do I revisit yarns.

Which is not to say that such endeavors wouldn’t be rewarding. There are myriad volumes surrounding me on a daily basis that I have relished inordinately in the past, and I frequently imagine the delights sure to be realized from a repeat reading of, say, Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, or Gore Vidal’s Lincoln, or the full run of Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther crime novels. Robert Wilson’s The Blind Man of Seville beckons to me each time I pass it in my office, as do T.C. Boyle’s Riven Rock, Lisa Grunwald’s The Theory of Everything, and Stephen Price’s By Gaslight. Yet I am focused, instead, on whatever works must be consumed in relation to my latest assignment.

This year, however, those priorities are in for a change. I am devoting the first six months of 2023 (or perhaps longer) to reading or rereading books that already decorate my walls; the majority of new releases will have to await my subsequent notice.

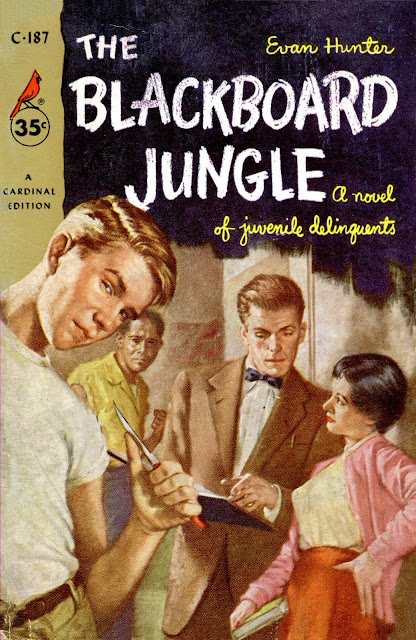

While I haven’t identified all of the individual works to receive my renewed attention, I have selected the first series to rediscover: A.B. Guthrie Jr.’s half-dozen western historical novels, penned between 1947 and 1982, but republished in paperback by Bantam Books

during the early ’80s. Those are the editions I own, all gently thumbed and generally pristine looking. Ready for me to pick up and sink into once more.

during the early ’80s. Those are the editions I own, all gently thumbed and generally pristine looking. Ready for me to pick up and sink into once more.(Right) Author A.B. Guthrie Jr.

My initial experience with this sequence of large-canvas, character-rich tales—focused on “the Oregon Trail and the development of Montana from 1830, the time of the mountain men, to ‘the cattle empire of the 1880s to the near present,’” as Wikipedia explains—came shortly after college, when I was living by myself in an apartment with no television for distraction. I was then a bigger reader of western fiction than I am today, but my guess is that I was initially drawn to these releases by their consistent design format and wraparound covers.

The stories had much to commend them, as well. They’re rich in adventure and a palpable love of the expansive American West, though a West that’s already losing its untouched-frontier luster. The Big Sky, which was published originally in 1947, tells of Boone Caudill, the short-tempered son of an abusive father, who flees his family home in Kentucky and sets off west for the sunset lands, dreaming of life as a mountain man. He eventually does get into fur trapping, moves progressively further from civilization, takes up with a comely Blackfoot woman, but finds that happiness and freedom have a habit of eluding him. As Montana historian Keith Edgerton explained in an essay for Fifty Years After the Big Sky: New Perspectives on the Fiction and Films of A.B. Guthrie, Jr. (2001), Guthrie

set the novel [largely] in the mid-1830s upper Missouri drainage, centering on the exploits (and exploitations) of several fur trappers on the make from back east. But they’ve arrived just a trifle too late; mostly the streams have been trapped out by earlier voyagers (“expectant capitalists” in the words of historian Richard Hofstadter). They are rough men, ruthless, violent, completely lacking in any of the romance, mythic nobility or Gabby Hayes hokum that undergirded most of western literature and Hollywood film up to that point and beyond. As one of Guthrie’s minor characters exclaimed, “She’s gone, goddamn it! Gone. ... The whole shitaree. Gone, by God, and naught to care savin’ some of us who seen’er new.” Paradisiacal Montana (Edenic only for an illusory and relative momentary speck of time) is lost. And “fallen” Montana now overshadows and signifies much that will follow in our literary and historical conceptions of the place and its people. The boom of the fur bonanza echoed only a mere twenty or so years; gold, silver, copper, wheat, cattle, and now coal and oil, all have followed the pattern since,Alfred Bertram “Bud” Guthrie Jr. (1901-1991) brought both a fictionist’s curiosity and his clear-headed affection for the 41st state to the penning of these volumes. As a child, he’d taken his earliest breaths in Bedford, Indiana, but within half a year had relocated with his parents to Montana. After graduating from the University of Montana, he moved again, this time to Lexington, Kentucky, where he accepted a reporting job with what was then the Lexington Leader newspaper (today’s Lexington Herald-Leader). He eventually served there as city editor and an editorial writer. Guthrie published his debut novel, the whodunit Murders at Moon Dance, in 1943, and in the next year, won a Nieman Fellowship from Harvard University. It was during his time studying writing in Boston that he began work on The Big Sky. Following its release in ’47, he departed the Leader and went to the University of Kentucky to teach creative writing; he would remain in education until 1952, when he finally returned to Montana and assumed the role of full-time fiction author.

Building on the success of The Big Sky, Guthrie penned five sequels: The Way West (1949, and winner of the 1950 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction), These Thousand Hills (1956), Arfive (1971), The Last Valley (1975), and Fair Land, Fair Land (1982). The Big Sky, The Way West, and Fair Land, Fair Land make up a trilogy of their own, leading to the deaths of both Caudill and Dick Summers, a hired guide introduced in The Big Sky and a principal player in The Way West.

Although he penned half a dozen more western mysteries during his lifetime (notably 1974’s Wild Pitch), as well as several non-fiction works and a 1960 short-story collection titled The Big It, Guthrie remains best remembered for his western historicals.

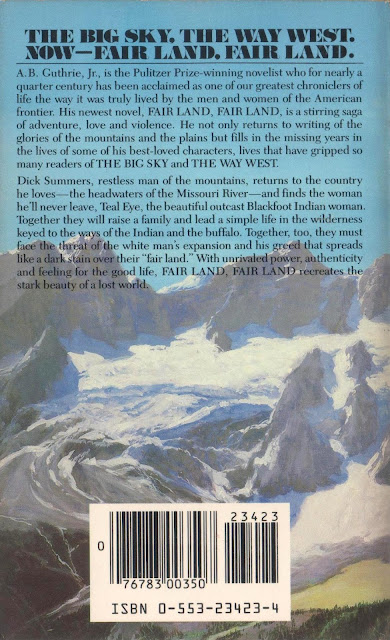

Most of these novels went through multiple paperback editions, but for my money, the finest versions were those Bantam brought to market in the ’80s. All but one (The Last Valley, credited to Gordon Crabbe, who also painted fronts for Louis L’Amour) featured imagery by Louis S. Glanzman. Scans of my collection are below.

Click on any of these images for an enlargement.

Artist Louis Samuel Glanzman (1922-2013) was born in Baltimore, Maryland, but reared in Virginia, until the Great Depression sent his family—including parents Gustave and Florence Glanzman—north to Rockaway, New York. As Canadian artist Leif Peng explained in his Today’s Inspiration blog back in 2009, Glanzman “began his professional art career [at age 16] as a comic book artist. He created a back-up feature called ‘The Shark’ in Centaur Publications’ Amazing-Man Comics,” and later painted covers for that comics line. (His younger brother, Samuel Joseph Glanzman, would go on to become a prominent comics artist himself.) Lou was quoted in a 2013 Muddy Colors tribute as recalling,

“I got my art training in comics. I did go to the School of Industrial Arts in New York, but most of the time I played hooky at the burlesque shows on 42nd Street.”

“I got my art training in comics. I did go to the School of Industrial Arts in New York, but most of the time I played hooky at the burlesque shows on 42nd Street.”(Left) Glanzman’s cover for Pippi in

the South Seas (1959).

Such truancy apparently didn’t do him any long-lasting damage. During the Second World War, Lou Glanzman served stateside with the Army Air Corps as a mechanic working on trainer aircraft, and also took illustration assignments from Air Force Magazine. After being discharged from the service, he sought additional artistic work, but was told repeatedly he should “go back to school” if he hoped to succeed in the business. Glanzman said he got his “first big break” with the men’s magazine True. From there he got into doing art for children’s books, including the Tom Corbett, Space Cadet series and Swedish author Astrid Lindgren’s best-selling Pippi Longstocking books. At age 31, in 1953, he was accepted into the New York City-based Society of Illustrators, which surely helped him make contacts for a prolific freelance illustrating career that would see his paintings appear in such periodicals as Collier's, Readers Digest, Argosy, Boys’ Life, National Lampoon, Saturday Evening Post, National Geographic, and Time. He even did a brief stint as a court reporter for Life. (Click here for a selection of Glanzman’s magazine art.)

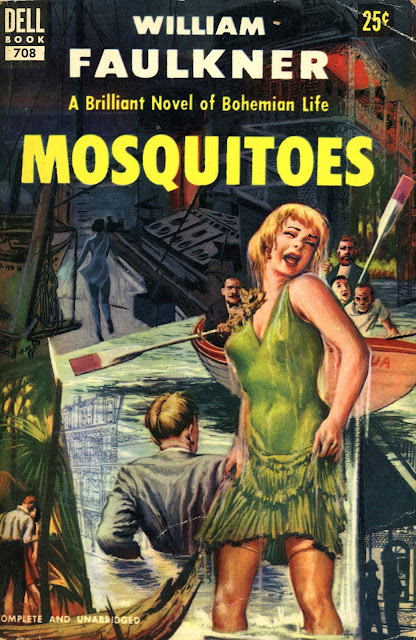

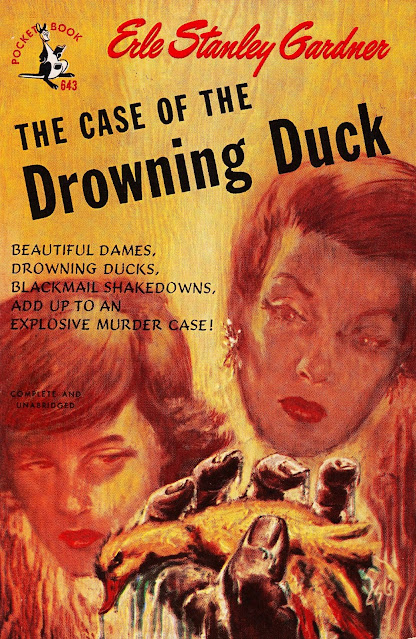

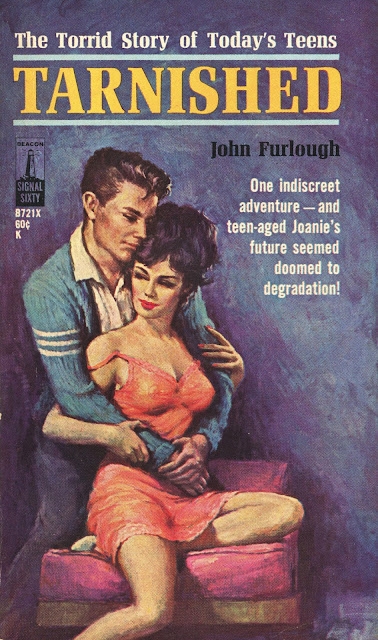

Several times over the years I’ve included examples of Glanzman’s artistry in this blog. But only recently have I explored the range of his book-cover illustrations. A.B. Guthrie’s novels represent only a fraction of his efforts. He painted fronts, as well, for science-fiction yarns, historicals by Louis L’Amour and Donald Clayton Porter, stories by P.G. Wodehouse and William Faulkner, and—most interesting to yours truly—paperback editions of crime and mystery fiction by Carter Dickson, Erle Stanley Gardner, Vin Packer, Kelley Roos, and others. Cataloguing the entirety of his output would be challenging, but scroll down to enjoy a few more examples of his creativity.

%20-%20illus%20Louis%20Glanzman.jpg)

,%20Bantam%20Books%201956%20-%20illus%20Louis%20Glanzman.jpg)

%20-%20illus%20Louis%20Glanzman.jpg)

,%20Pocket%201949%20-%20Cover%20art%20by%20Louis%20Glanzman.jpg)

With so much on his plate, it seems a wonder that Louis Glanzman found time to paint those powerful, so-well-remembered covers for A.B. Guthrie’s western historicals. I’m just glad he did.

%20features%20Robert%20Maguire's%20first%20paperback%20cover%20-%20teen.jpg)