It’s one of the offenses I remember best from my early schooling. During the spring of my seventh-grade year (or maybe it was eighth grade), a group of boys from my class decided to take advantage of a maintenance truck that had been parked innocently beneath the high windows of the girl’s gymnasium locker room. While others of us were busy in class, those scallywags scampered to the top of that vehicle and slowly lifted their wide eyes above the windowsill. I don’t know how long they remained unseen, but once discovered, their presence set off shrieks that threatened to shatter glass throughout that level of the school. Even before the young ladies caught bare-assed and red-faced could formally complain (along with their mothers) about such indignities, our very proper female principal had identified the guilty parties and called them on the carpet. I don’t remember what disciplinary actions followed, but I do recall thanking my lucky stars that I had not been invited to take part in this pubescent prank. At the least, it saved me from having to endure the ugly looks—and I do mean

cut-off-your-balls ugly—that those embarrassed misses shot at the offenders each time they passed them in the echoing hallways.

It was from that incident that I learned the meaning of “Peeping Tom.” However, the term goes back much farther in history, to the legend of

Lady Godiva. According to the tale, Godiva was the wife of an 11th-century Anglo-Saxon nobleman who had recently imposed onerous taxes on the residents of Coventry, in England’s West Midlands region. Sympathizing with the locals, she asked her hubby to roll back the levies. Finally wearying of her repeated entreaties, he agreed to do so—but only if she would ride a horse naked through the Coventry streets. Godiva took him up on the dare, but first ordered that the townspeople remain inside and shutter their windows. Everyone obeyed, it’s said, except for a tailor who couldn’t resist a glimpse of the noblewoman’s beauty as she trotted by concealed only in her cascading tresses. The story has it that Godiva’s husband made good on his promise, while the reckless voyeur—thereafter known as Peeping Tom—was struck blind for his transgression.

Usually voyeurism doesn’t result in one losing his or her eyesight. (Thank goodness!) But it can lead to legal action. Only this last summer, for instance, a video circulated on the Internet showing

Erin Andrews, a 31-year-old ESPN-TV sideline reporter, curling her long blond hair and putting on makeup while standing nude in front of a hotel mirror. The quality of the image wasn’t great, but that’s partly because it was shot without the subject’s knowledge, through a modified hotel room keyhole. When Andrews learned of this footage,

she complained of invasion of privacy, and ESPN made an effort to strike the video from numerous Web sites. Just last week, 48-year-old

Michael David Barrett was arrested

in Chicago for stalking the ESPN “siren” and shooting eight videos of her through hotel keyholes in Nashville, Tennessee, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

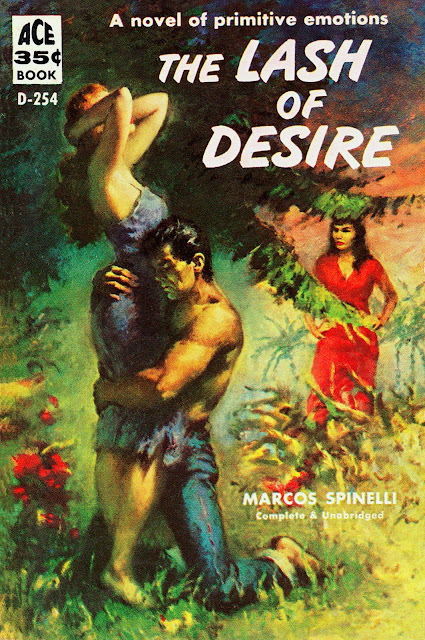

The Andrews saga sent me back to my collection of vintage paperback jackets. Believe it or not, the 20th century produced a whole genre

of “Peeping Tom covers.” Some decorated cheap books designed for “adult reading,” including a number by the prolific

Orrie Hitt (

The Peeper,

I Prowl by Night,

Too Hot to Handle,

The Love Season,

Peeping Tom, etc.). Others fronted works by Clifton Adams (

Whom Gods Destroy),

Harold Q. Masur (

Bury Me Deep), and Stephen Ransome (

Some Must Watch). A couple of specimens were added in more recent years by Hard Case Crime (

House Dick, by the notorious

E. Howard Hunt, and

The Last Quarry, by Max Allan Collins)—obvious odes to the genre, conceived by publisher

Charles Ardai and his team of talented artists.

Within this genre of book covers, there seem to be three predominant varieties. The first type offers glimpses of titillating action through keyholes—the sort of action Ms. Andrews’ stalker was undoubtedly hoping to capture. Jay de Bekker’s

Keyhole Peeper (Beacon, 1955)—shown at the top of this post—is a splendid example. “De Beeker” was in fact a pseudonym used by pulp novelist

Prentice Winchell (1895-1976), who also published as “Spencer Dean” and, perhaps most memorably, as “Stewart Sterling.”

For more than two decades, from the early 1940s through the mid-’60s, Winchell wrote New York City-based series featuring fire marshal Ben Pedley (

Five Alarm Funeral), department store troubleshooter

Don Cadee (

The Scent of Fear), and Manhattan hotel security chief

Gil Vine (

Dead Right, aka

The Hotel Murders). The author evidently had a particular interest in

hotel sleuthing; in 1954, he and co-author Dev Collans published

I Was a Hotel Detective, a non-fiction work described as “a startling exposé of life in a big-city hotel.”

Keyhole Peeper appears not to be a Vine book, but instead a standalone novel. “A house detective spills his guts,” announces its front-cover teaser. “Behind every door lay a temptation!” Another description of the story’s plot reads: “It was not easy for Holcumbe to make the grade as house detective. Day and night he had to cope with party girls,

hustlers, con men ... but toughest of all was his battle with himself.”

At least, if we’re to judge from the jacket of

Keyhole Peeper, he didn’t lack for entertainment during the course of that battle.

The second sort of Peeping Tom cover involves windows (or, alternatively, doorways) through which men or women catch furtive, often hungry ganders at other people in various stages of undress, romantic endeavor, or other normally private activity. There are many such book fronts, though few are quite as distinctive as the façade of Bantam’s 1949 edition of

Dead Ringer, by

Fredric Brown (an entry in his

Ed and Am Hunter private-eye series). One of my personal favorites is Frances Loren’s

Bachelor Girl (Beacon, 1963), with a painting by Robert Maguire. It’s unusual in that the person treated to a surreptitious sighting of supple feminine flesh through glass is the reader, rather than some character in the book.

Finally come the jackets, such as that on Max Collier’s 1962 novel,

Thorn of Evil (illustrated by

Paul Rader), in which folks avail themselves of salacious perspectives from behind bushes, camera lenses, curtains, transoms, and such. And somehow they all get away with it—unlike my curious grade-school classmates.

The talents of many familiar artists are represented in the paperbacks featured below. Beyond works from Maguire and Rader, you’ll find cover

paintings by George Ziel,

Robert McGinnis, Griffith Foxley, Rudy Nappi, Victor Kalin, Tom Miller, Lou Marchetti, Stanley Borack, James Meese, Darrel Greene,

Glen Orbik, Fred Fixler, George Gross, James Avati, Casey Jones,

Mitchell Hooks, Barye Phillips, Bill Edwards, Al Rossi, Charles Binger, Robert Stanley, Bernard Safran, Verne Tossey, and of course

Robert Bonfils (who gave us no fewer than half a dozen of these book fronts—many of the “not safe for work” specimens—including

Sex Cinema,

Swapping Cousins, and the deliciously titled

Night Train to Sodom).

All I can say, before you scroll down any further, is “enjoy the view.” Just click on the covers to bring up enlargements.

Incidentally, I am indebted to a couple of Web sites for putting me on the trail of some covers highlighted here: Vintage Paperbacks: Good Girl Art, where I discovered

several of the jackets featured in this post; and

Pulp Covers: The Best of the Worst, which offers an amazing variety of vintage book and magazine illustrations. Thanks, as well, to veteran critic and Rap Sheet contributor

Dick Adler, who added one or two novel fronts to my trove.

READ MORE: “

Too

Hot to Handle by Orrie Hitt (Beacon, 1959),” by Michael Hemmingson (Those Sexy Vintage Sleaze Books).